This piece delves into the private health sector’s role in combating Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in India and proposes the need for a formal accountability instrument for AMR.

In the face of major global health challenges and the recent pandemic, Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) stands out as a growing threat, claiming 5 million lives each year and demanding urgent attention from all levels of society. As the world grapples with the consequences of inappropriate use and disposal of antimicrobials such as antibiotics and the subsequent rise of resistant strains of microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.), also called ‘superbugs’, the role of the private sector in addressing this crisis cannot be overstated.

When it comes to AMR, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like India face a particularly complex scenario due to their large population and diverse healthcare challenges. According to the World Bank, the material risk of AMR would result in global output losses of more than USD 1 trillion by 2030 and USD 2 trillion by 2050 and push 28 million people into poverty if remains unchecked. Half of the world’s poor live in just 5 countries, which includes India, and would be the first to bear the brunt of infectious outbreaks like AMR.

Not only is India a major consumer of antibiotics, but in 2012, the country produced a third of the global antibiotics, and that has only increased since. Simultaneously, India grapples with issues such as inadequate healthcare infrastructure, limited access to quality healthcare, particularly in rural areas and urban slums, and various socioeconomic factors influencing healthcare outcomes and burden.

In this context, despite an unclear regulatory environment in India, businesses involved in both antimicrobial manufacturing and healthcare have a distinctive responsibility to address AMR in a manner that is both globally relevant and locally impactful. The Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR) framework, launched in 2012 by the Indian regulator SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India), is a good accountability and monitoring tool, but whether it is adequate for AMR accountability remains to be seen.

Major private actors in the health sector

Pharmaceutical companies

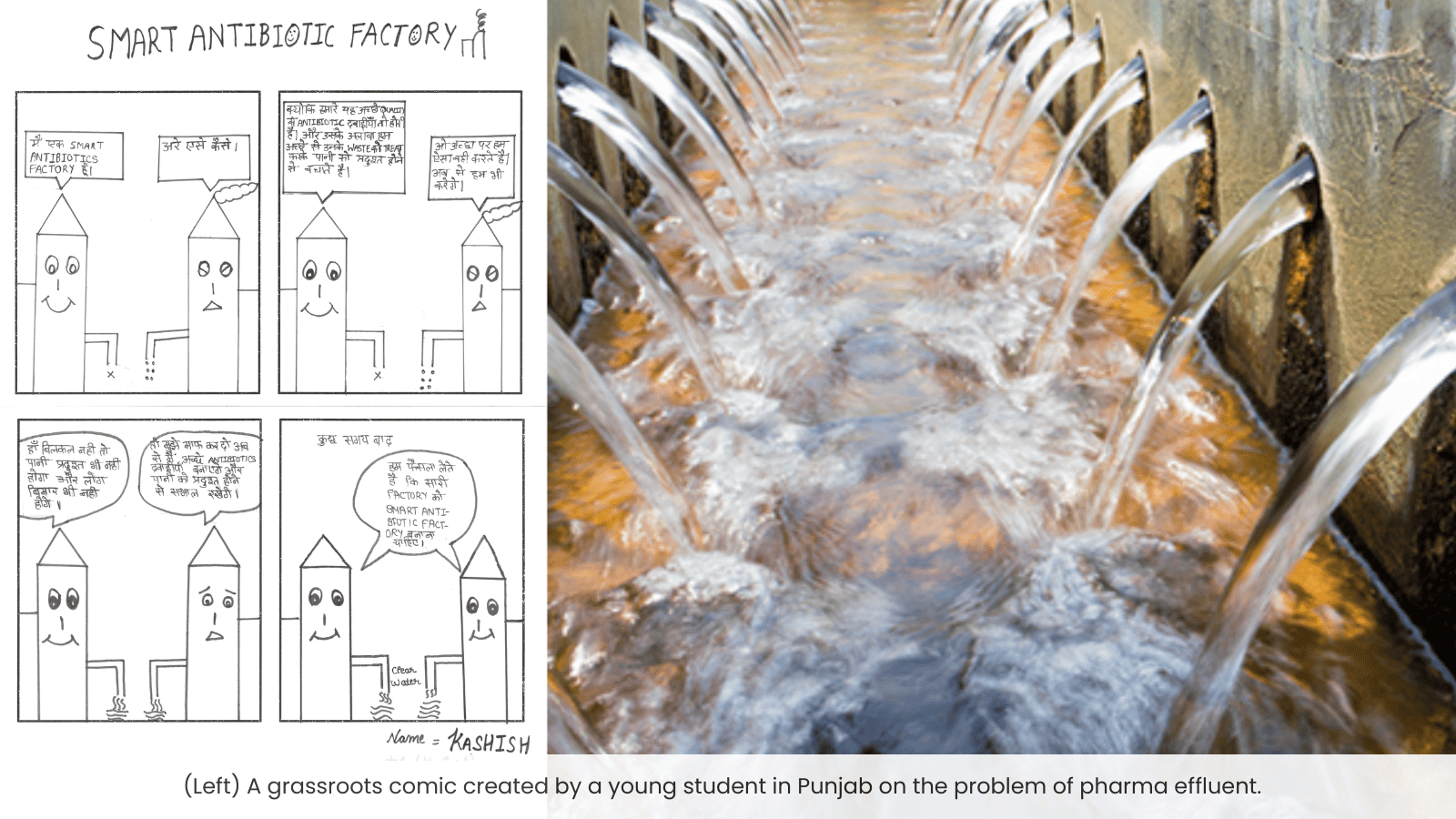

Pharmaceutical companies, particularly those manufacturing antibiotics, have a great deal of responsibility for preventing the rise of AMR. Waste created at a production site is typically dumped into rivers and waterways during the antibiotic manufacturing process. If this wastewater contains high quantities of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), it poses a significant danger to the rise and spread of AMR. A stark example of this was seen in a 2017 report of the Kazipally industrial area in Hyderabad, a pharmaceutical hotspot, where the water bodies were brimming with pharmaceutical effluents containing antibiotic residues, among other drugs, as well as superbugs. This endangers not only human lives but also the larger environmental ecosystem.

A 2023 study conducted by the Netherlands-based Access to Medicine Foundation revealed encouraging developments in the country. Notably, major pharmaceutical companies in India have demonstrated a robust commitment to implementing Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) at their owned and operated manufacturing sites. This signifies that no antibiotic waste is discharged into local waterways, reflecting a positive step towards environmental responsibility.

However, just 21 of the 82 pharmaceutical and healthcare businesses in the most recent BRSR report—which comprises 1000 listed companies—have acknowledged AMR or mentioned their efforts to tackle AMR. While both the studies primarily focused on big pharmaceutical companies, it is equally, if not more, crucial to scrutinise smaller pharmaceutical firms that may occasionally elude regulatory scrutiny.

Private healthcare facilities

One often hears how a hospital visit or stay resulted in a Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) or pneumonia. In fact, a recent study showed that the global number of hospital-acquired resistant infections is about 136 million per year, with China (52 million), Pakistan (10 million), and India (9 million) bearing the heaviest burden. In fact, the risk of acquiring hospital-acquired infections is up to 20 times higher in LMICs. It therefore comes as no surprise that hospitals are a major hotspot of AMR, serving as an important frontline for AMR control and prevention.

A large proportion of our country’s population receives healthcare at secondary and tertiary private hospitals, which frequently lack adequate infection prevention and control measures. This, combined with the high use of antibiotics in medical procedures, makes hospital settings a prime location for the development and spread of AMR. With the private healthcare sector accounting for nearly 62% of all health infrastructure in India, it is a significant contributor to and combatant of AMR.

Pharmacies

Pharmacies in India are often seen doling out healthcare advice along with drugs. The easy availability of over-the-counter (OTC) antibiotics for personal use in India is also cited as one of the key drivers of AMR. Even though the per-capita private-sector consumption rate of antibiotics in India is relatively low compared to many countries, India consumes a large volume of broad-spectrum antibiotics that should ideally be used sparingly, as well as a large volume of antibiotics not approved by the central drug regulators.

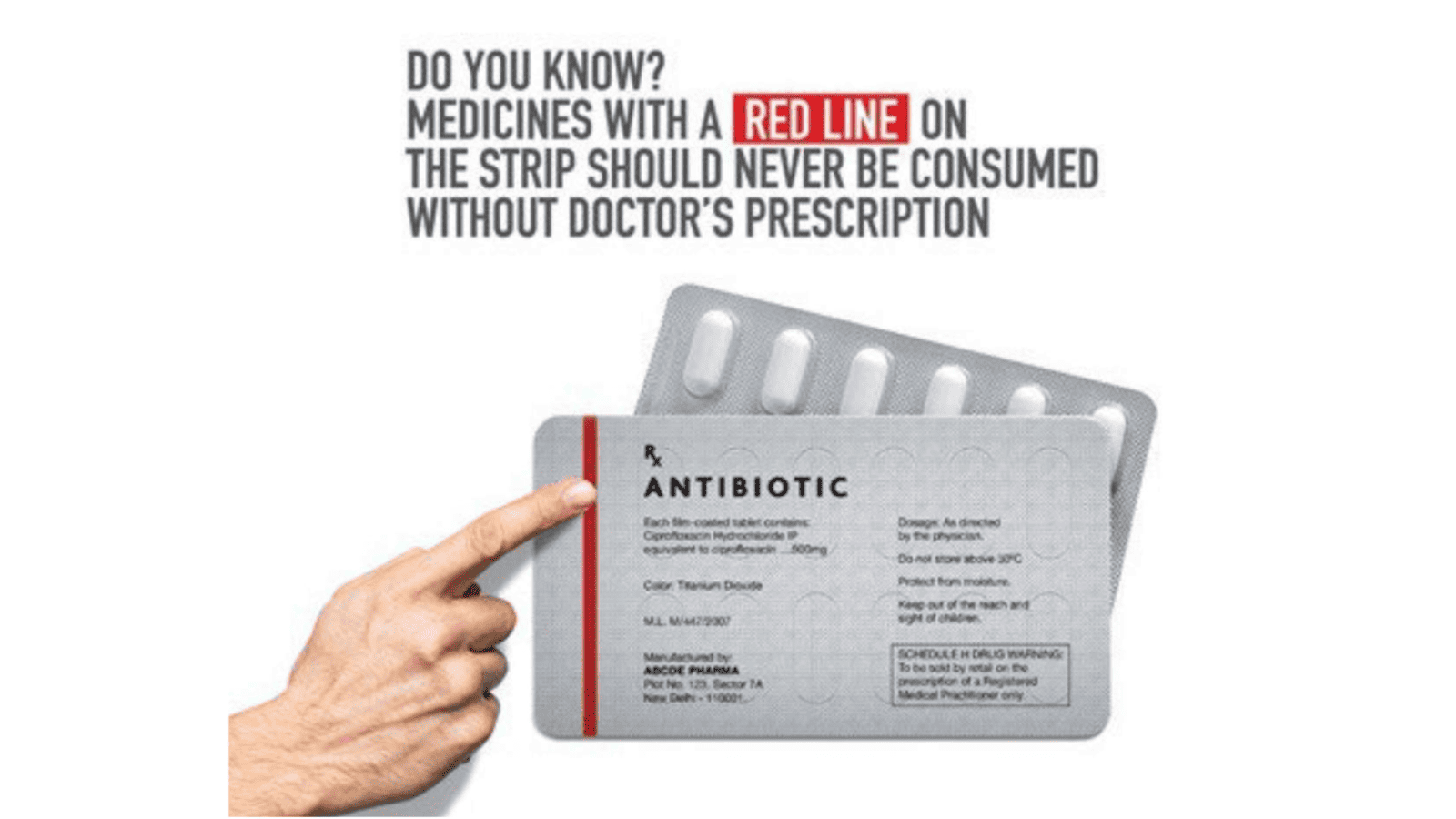

Despite regulatory restrictions such as the ‘red line’ on prescription drugs, many privately operated pharmacies that have proliferated over the years in the country routinely disregard these policies. Antibiotics, intended for prescription use only, are often sold without a doctor’s prescription, treating them akin to painkillers and other non-prescription medications. This not only violates established regulations but also introduces a new layer of complexity to the problem of AMR. Due to this unregulated and undocumented use, surveillance of antibiotic use and AMR assumes significance in detecting hotspots.

This is not an exhaustive list of AMR contributors or offenders; it’s crucial to recognise that private players contributing to the issue of AMR extend beyond those in healthcare. For instance, companies engaged in animal farming and agriculture, where substantial amounts of broad-spectrum antibiotics are employed, must also be held accountable for their role in the spread of AMR. This underscores the need for a comprehensive approach that includes diverse industries to address the multifaceted nature of AMR and foster responsible practices across various sectors.

Regulatory chaos

Despite various national and state-level AMR action plans, antibiotic monitoring is almost nonexistent in India. In the absence of comprehensive and strictly enforced regulations for addressing antimicrobial use, manufacturing practices, and surveillance, controlling AMR will remain far-fetched. Similarly, without clear guidelines, private sector stakeholders may also lack the necessary incentives to adhere to best practices in combating AMR.

These challenges are further underscored by the economic considerations of these businesses, fragmented pharmaceutical supply chains, limited access to healthcare in rural areas, and constrained research and development efforts. To tackle these issues, a collaborative effort involving regulatory bodies, healthcare professionals, and the industry is essential. This collaboration should focus on establishing clear guidelines, enhancing education, and promoting responsible antibiotic use throughout the healthcare ecosystem.

In addition, attention must be given to the old and sinister nexus between pharma, hospitals, and pharmacies in dispensing and prescribing antibiotics. While it has not reached epic proportions in India as in countries like the USA, the potential escalation of profit-driven decisions over health and well-being requires stringent regulations and monitoring to prioritise human health over financial incentives.

CARE (Corporate AMR Responsibility) for the future

Responsible manufacturing practices play a pivotal role in addressing the global challenge of AMR. This involves not only adopting environmentally friendly processes and minimising waste but also ensuring that the production of antibiotics aligns with global guidelines for responsible use. To contribute effectively to the fight against AMR, businesses can integrate these practices into their operations and transparently disclose their efforts.

ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) reporting has emerged as a crucial mechanism for large companies to communicate their commitment to sustainability and responsible business practices. ESG encompasses a broad spectrum of factors, extending beyond traditional financial metrics to include environmental impact, social responsibility, and governance practices. Companies that report on these elements provide stakeholders with a comprehensive view of their operations and their impact on the world. In the context of India, the government’s Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting should give special focus to efforts addressing AMR.

Furthermore, it is imperative to increase involvement from hospitals and healthcare professionals as stewards of antimicrobials, which have undeniably revolutionised modern medicine. This responsibility involves actively adhering to and advocating for the optimal use of these crucial drugs, championing infection control measures, as well as proactive surveillance of resistance to curb the rising threat of AMR.

In light of the ongoing global recovery from the economic and social impacts of the COVID pandemic, there is an urgent need for investors to prioritise infectious diseases and incorporate AMR-related metrics into their investment decisions. By doing so, they can incentivise companies and healthcare settings to prioritise responsible practices, thereby mitigating the risk of another global outbreak. Consequently, ESG or a similar objective reporting framework can become a powerful tool for companies to attract responsible investment, aligning business objectives with global health priorities and contributing to the collective effort against AMR.

—

Sarah Hyder Iqbal is the co-founder and lead of Superheroes Against Superbugs initiative