Since their discovery, antibiotics have saved millions of lives, making surgeries safer and supporting treatments for cancer and chronic illnesses. But decades of overuse and misuse by us are now fueling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)—a public health crisis where infections no longer respond to treatment with antimicrobials like antibiotics. In countries like India, which are not only hotspots for AMR but also grappling with poor sanitation and health systems, losing the effectiveness of these life-saving medicines is not an option. To keep them working, we must understand how they work and use them wisely.

A happy accident and a timely warning

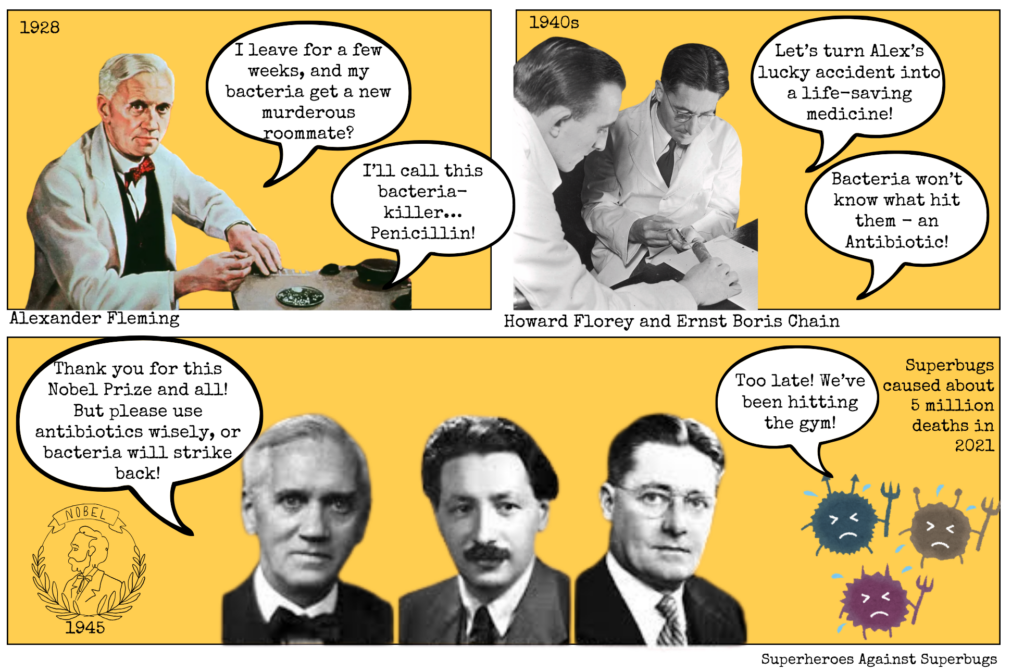

In 1928, Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming returned from vacation to find that a mould, Penicillium notatum, had killed bacteria in one of his petri dishes. This accident led to the discovery of penicillin, the world’s first true ‘antibiotic’—a term first used by Selman Waksman in 1947 to describe small molecules made by microbes that inhibit others.

This serendipitous discovery alone wasn’t enough, as the microbes produced only small amounts of antibiotics—insufficient for human use. It took the efforts of two other scientists, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain, to develop a method for mass-producing penicillin during World War II. By the 1940s, it was saving thousands of wounded soldiers and, soon after, millions of civilians, forever changing the course of medicine and human society.

Fleming, however, gave a warning while accepting his 1945 Nobel Prize along with Florey and Chain: overusing antibiotics would allow bacteria to become resistant to their effects. This is because antibiotics create ‘selection pressure’, killing some bacteria while allowing resistant ones to survive and multiply. Misuse speeds up this process, leading to superbugs that are resistant to the toxic effects of antibiotics.

Just a few years later, in 1947, the first penicillin-resistant infection was detected. More than 70 years on, close to 5 million deaths worldwide are attributed to these antibiotic-resistant infections, and if no action is taken, this number is predicted to increase by 70% by 2050.

How antibiotics work—and why it matters

Antibiotics have their origins in nature, as Alexander Fleming’s discovery revealed. Long before they were discovered, bacteria and fungi were already producing these powerful compounds in small amounts as a survival tactic to outcompete other microbes.

Antibiotics work by disrupting their growth—either by killing them outright (bactericidal) or preventing them from multiplying (bacteriostatic). They do this by targeting essential bacterial functions, such as cell wall synthesis, protein production, or DNA replication.

While many antibiotics were originally derived from natural sources, modern antibiotics are often semi-synthetic or fully synthetic, designed to enhance efficacy and combat bacterial resistance to them. Based on their chemical structure, mechanism of action, and the type of bacteria they target, antibiotics are classified into different classes: beta-lactams (such as penicillins and cephalosporins), macrolides (like erythromycin), tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and glycopeptides (such as vancomycin).

Antibiotics can be further classified as broad-spectrum, working against many bacteria, while others are more selective and are known as narrow-spectrum. Doctors prefer narrow-spectrum antibiotics whenever possible, as they cause less harm to beneficial bacteria (like those in the gut). However, in cases where the bacterial culprit is unclear or the infection is severe, broad-spectrum antibiotics may be necessary. This careful clinical approach also helps prevent bacteria from learning how to fight back against antibiotics, making antibiotic treatments more effective in the long run.

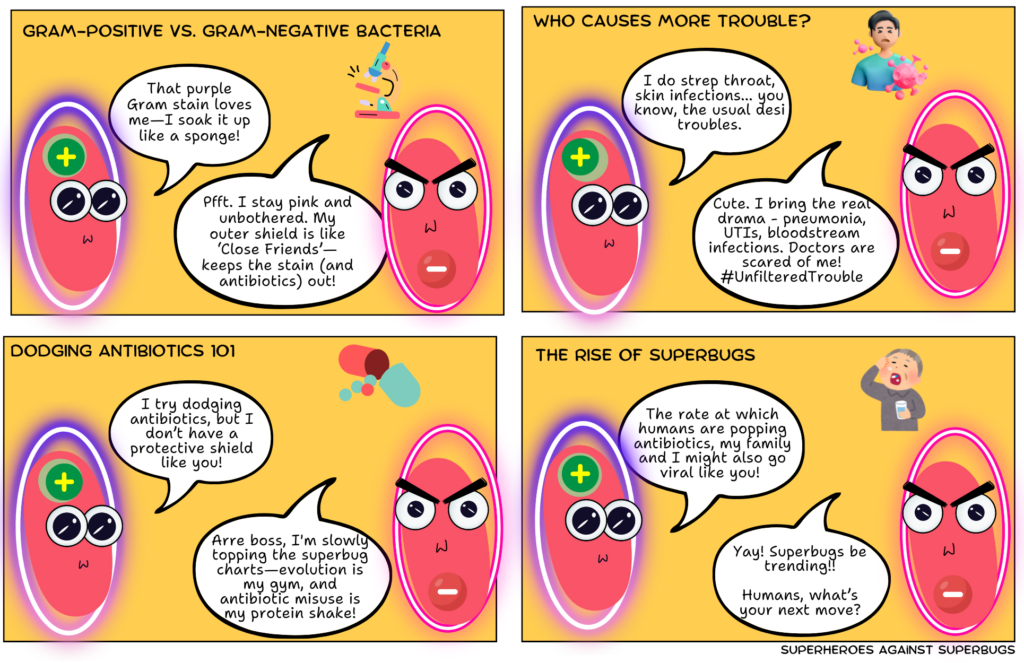

Designed to resist

Bacterial structure plays a big role in how well these drugs can target and destroy them. Some bacteria, known as Gram-positive, have thick cell walls and are typically easier to treat with antibiotics, though some strains have developed resistance. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner cell wall but an additional outer membrane that acts as a protective barrier, making them inherently more difficult to treat. Many Gram-negative bacteria, including those causing urinary tract infections and pneumonia, have acquired resistance to multiple antibiotics, posing a serious challenge for doctors.

But bacteria are able to quickly evolve through genetic mutations and gene exchange making them adept in evading antibiotics designed to kill them. The overuse of antibiotics is giving bacteria more chances to get better at resisting these drugs. Today, many bacteria have even developed resistance to multiple antibiotics (multi-drug resistance).

As bacteria find new ways to survive, scientists are in a constant race to develop treatments that still work, while doctors struggle to keep up with dwindling options.

Choosing the right antibiotic—not a guessing game

With the complexity of how antibiotics work and bacteria’s natural ability to develop resistance to them, choosing the right antibiotic is never a matter of guesswork—nor should it be a decision made without a doctor’s advice. When a patient has an infection, doctors often prescribe antibiotics based on their symptoms, medical history, and how certain infections have responded in the past. If the infection does not improve or is serious, they may send a sample to a lab for testing. In the lab, the bacteria causing the infection can be identified, and tests can tell doctors which antibiotics will work best.

In some cases, newer, faster molecular tests can even identify signs that infection-causing bacteria are becoming resistant to the effects of certain antibiotics, helping doctors choose the most effective treatment sooner. Doctors often start with a general antibiotic and then switch to a more targeted one once test results are available. This way, doctors ensure that the infection is treated effectively while reducing the risk of AMR.

Be AWaRe of antibiotic misuse

To help doctors and the healthcare community at large to slow the rise of AMR, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the AWaRe classification system in 2017 as part of its Essential Medicines List.

As per this, antibiotics are divided into three groups: The Access group includes first-choice antibiotics for common infections, with a lower risk of resistance. The Watch group consists of antibiotics that should be used more cautiously because they have a higher chance of causing resistance. The Reserve group includes the strongest antibiotics, meant to be a last resort when nothing else works.

Following this classification ensures that antibiotics remain effective for as long as possible, but it requires everyone—doctors, pharmacists, and patients—to take responsibility.

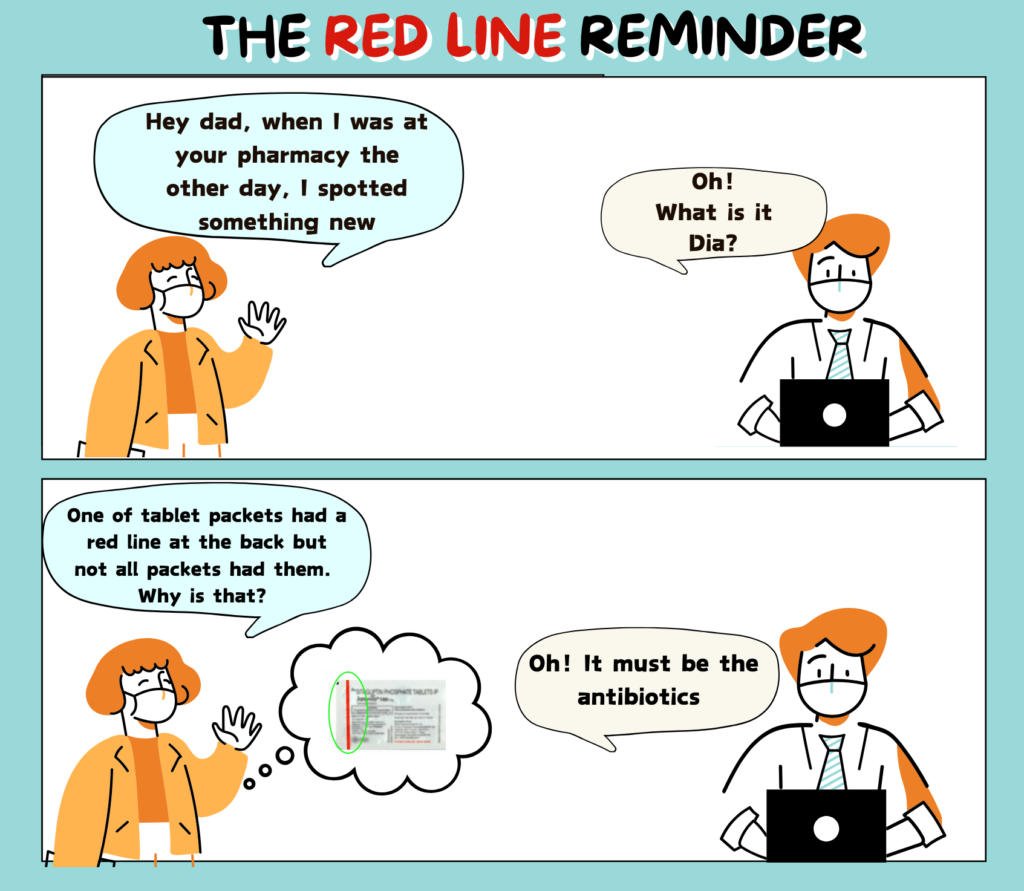

Did you know that the Government of India launched the Red Line Campaign in 2016? Today, many antibiotic packages in India carry a red line, warning consumers not to take them without medical advice. Read the full comic by Sanjukta Mondal, SaS here.

Be a smart antibiotic user

While bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a slow and unavoidable natural process, our actions have accelerated it into a full-blown public health crisis, making life-saving antibiotics lose their potency.

“The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself, and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant.” Fleming’s warning rings true particularly for India, where easy over-the-counter access to antibiotics has fueled misuse and rising AMR cases.

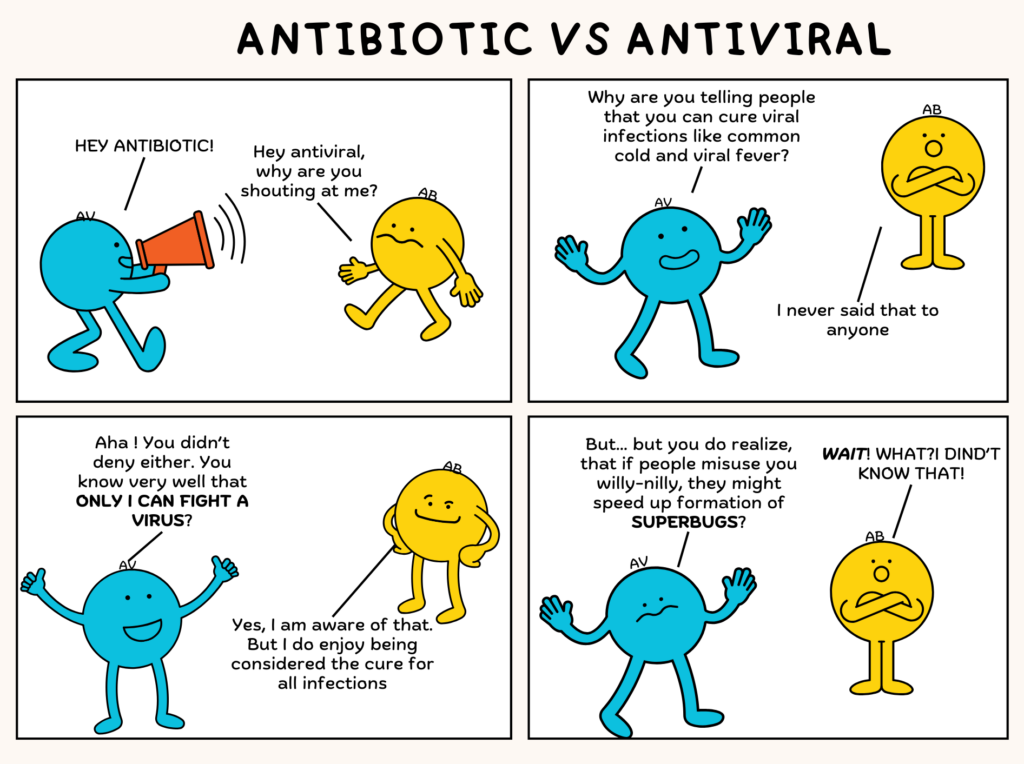

It’s easy to think of AMR as a problem for doctors and scientists, but our daily choices impact the future of these life-saving medicines. The most important thing to remember is that antibiotics don’t work against viruses. If you have a cold or flu, taking antibiotics won’t help. In fact, it will only give bacteria more chances to adapt and become resistant. So, never pressure your doctor or pharmacist for antibiotics when they aren’t needed.

Read the full SaS comic by Sanjukta Mondal here to learn why you should not use antibiotics to treat viral infections.

When prescribed antibiotics by your doctor, it’s important to complete the full course, even if you start feeling better, as stopping too soon allows surviving bacteria to mutate and become stronger. It’s also not a good idea to use leftover antibiotics or take ones meant for someone else—what works for one infection might not work for another, and the wrong antibiotic can do more harm than good.

Even better would be if we could help reduce the need for antibiotics by preventing infections in the first place. Simple steps like washing hands properly, getting vaccinated, and practicing good hygiene overall can significantly cut down on infections, reducing the need for antibiotics. Hospitals and municipalities must also step up infection control measures to prevent the spread of infections in healthcare and community settings.

Be a smart antibiotic user by understanding how they work and using them responsibly. The next time you reach for an unprescribed antibiotic, pause and ask: Do I really need this? Misuse today can mean no cure tomorrow. Protecting antibiotics isn’t just about your health—it’s about safeguarding your family, community, and the world.

Image credits: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; Mary Evans Picture Library; Nobel Foundation Archive.