How can thoughtful design influence the way we use antibiotics and encourage smarter, more responsible choices?

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the biggest global health challenges of our time, and India is at the heart of this crisis. The way antibiotics are accessed, prescribed, and used varies significantly across countries, and so do infection prevention practices, making it crucial to understand AMR in its specific cultural and systemic context.

I recently moved to the UK to pursue my master’s in service design. With my weak immune system and the UK’s unpredictable weather, it was only a matter of time before I fell sick—and I did. This was when I was faced with the reality of dealing with the UK health service provider, NHS, which seemed painfully slow compared to how healthcare works in India. This experience made me realise the differences between the two systems and led me to notice the pros and cons of both.

I realised that in the UK, people often don’t know the names of as many medicines, whereas in India, discussions about medicines are common, and most people can name several. When I asked people here to name an antibiotic, almost no one could—a stark contrast to what I was used to back home. Despite the flaws in the NHS, I believe it does a great job in safeguarding drugs like antibiotics and combating antibiotic resistance, a subset of AMR. However, as a service designer, I also understand that systems are entirely context-dependent. India is too large and culturally different from the UK, and it needs to create its own system that works for its unique context and culture.

This is why I chose to approach AMR through the lens of service design. As a service designer, I see AMR not just as a medical issue but as a systemic one, deeply intertwined with culture, behaviour, and accessibility.

AMR is what we call a “wicked problem”—a problem with so many interdependencies that it feels almost impossible to solve. There are many ways to approach it, and progress is incremental, but we can only move forward and make a dent in it.

Why service design?

In India, a vast majority of antibiotics sold are done so without a doctor’s prescription, purchased directly from pharmacies or even online. Meanwhile, many people lack awareness about AMR and continue to use antibiotics indiscriminately. Therefore, the solution does not lie in simply making rules—it’s about understanding why people behave the way they do and designing interventions that work within their daily lives.

Service design encourages zooming in and out to understand the system, its key players, and their relationships while co-creating solutions. It takes a human-centred approach, focusing on real behaviours rather than assumptions. By engaging multiple stakeholders—patients, doctors, pharmacists, and policymakers—it aligns interests and fosters collaboration.

Service design helps map the system and identify key touchpoints for targeted interventions. Through prototyping and iteration, these interventions can be tested, refined, and scaled, ensuring practical, sustainable, and impactful solutions.

The service design process

The design process is fairly chaotic in the beginning, but we as designers are taught to embrace the back-and-forth. It roughly follows the timeline of the Double Diamond framework. The Double Diamond is a design process model that consists of four phases: Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver. It’s visualised as two diamonds, with the first focusing on exploring the problem (divergent thinking) and the second on developing solutions (convergent thinking). This structure encourages designers to explore a wide range of possibilities before refining ideas into a clear and effective intervention.

Understanding AMR as a Systemic Issue

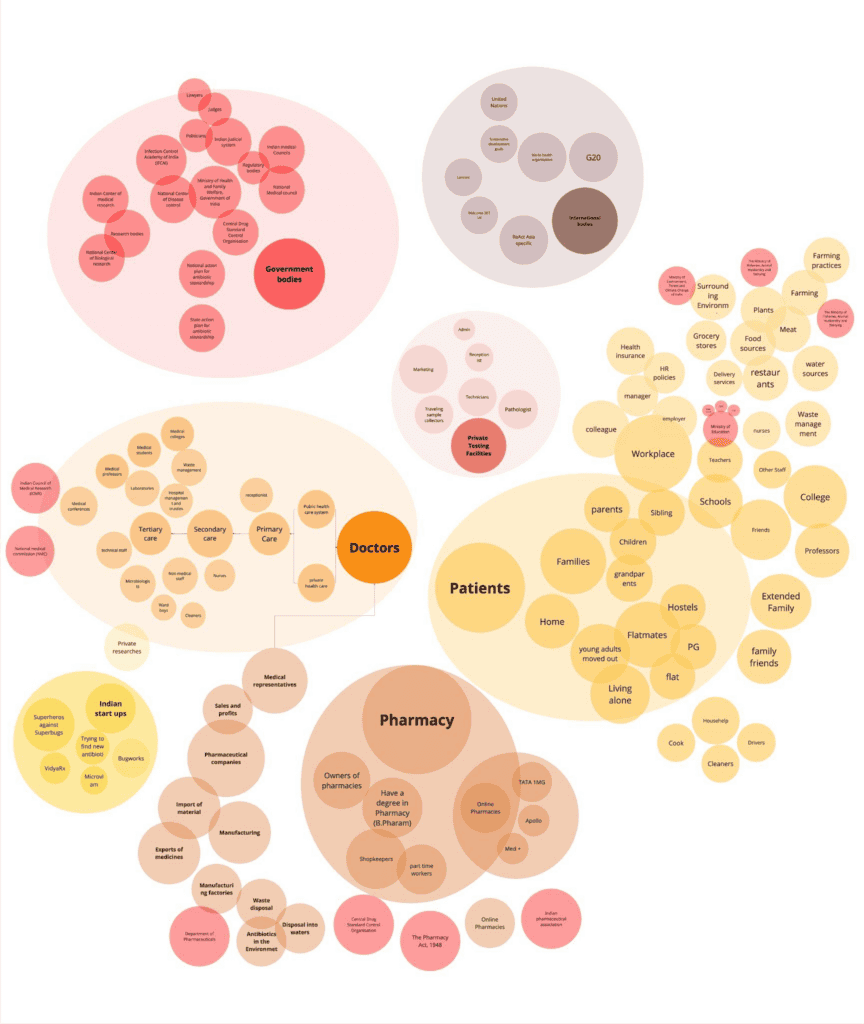

The first step in the process was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the AMR ecosystem, including its interdependencies and key players. This involved mapping the system, identifying stakeholder connections, and analysing the factors driving antibiotic misuse. I did this by having conversations with various people in the system (Figure 1).

In India, the AMR crisis is vast and deeply embedded in society, affecting everything from education and pharmaceutical waste disposal to regulatory oversight. Unregulated markets, overlapping authorities, and fragmented healthcare systems exacerbate the issue. Challenges like trust in governance, affordability, and access (either excessive or inadequate) create tensions, further worsened by socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

At times, the scale of the problem felt overwhelming—like any wicked problem, it seemed almost impossible to tackle.

Figure 1: Ecosystem map that captures the diversity of contexts and experiences that is used to narrow down to find solutions.

One thing that stood out while reading the National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (NAP-AMR) Module for Prescribers (2024) was that in 2011, 50 percent of antibiotics in India were sold without a prescription. While this data is somewhat dated, the lack of significant interventions suggests the situation may not have changed much. This prompted me to explore whether the same trend held true in urban populations. This curiosity led me to create a survey and conduct interviews within my social circle.

I focused on understanding how people take care of themselves when they are sick—what steps they follow, what medicines they keep at home, and how they decide on treatments. Why do people choose to self-medicate, even when they are educated and have easy access to doctors? From my interviews, I realised that young people who have moved away from home are more likely to self-medicate when sick.

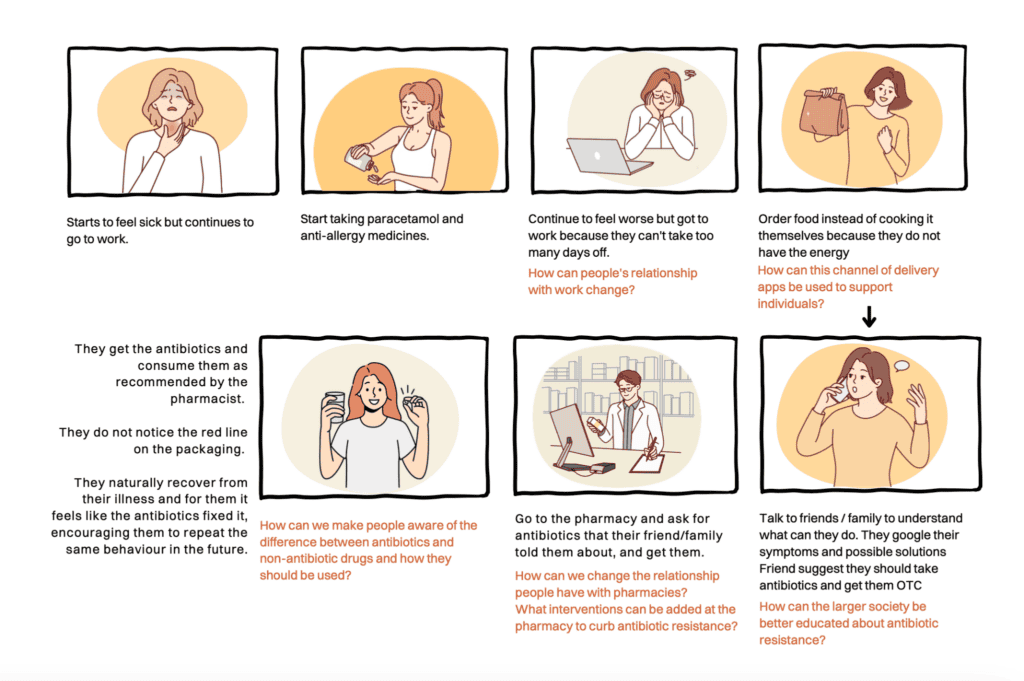

To analyse these insights, I created journey maps. A journey map is a tool used in service design to visualise the step-by-step experience of a user as they go through a process. It helps in identifying pain points, motivations, and decision-making moments.

In this case, the journey map allowed me to break down the typical process people follow when they get sick—from recognising symptoms to deciding on treatment. By mapping this out, I could better understand the barriers to seeking medical care and why self-medication was a preferred choice.

Figure 2: Condensed version of a journey map

Figure 2: Condensed version of a journey map

When co-creating these maps with young people, they often spoke about work and lack of support systems because they were in a new city.

This insight led to the creation of Thrive, a corporate wellness service that provides new employees with a wellness box to support them when they are unwell. The aim is to reduce antibiotic misuse by equipping employees with the right resources and supporting their self-care practices.

What’s in the Thrive Box?

- Curated self-care items (paracetamol, herbal remedies, soothing teas).

- A health information leaflet explaining common cold management and antibiotic resistance.

- A list of vetted doctors near the office for easy access to trusted healthcare.

- A QR code to order refills when applying for sick leave, reinforcing ongoing care.

By embedding education, support, and behavioural nudges into workplaces, Thrive can help employees take care of themselves before resorting to unnecessary antibiotics. This is a hypothetical service that I imagine, if implemented, would change the relationship people currently have in their workplace.

Thrive is not just about providing a wellness box—it’s about reframing how we care for ourselves when we’re unwell. By embedding care into workplaces, we can slowly change behaviours, reduce reliance on antibiotics, and promote responsible healthcare practices.

Designing Solutions for Systemic Change

Although the final solution is still imaginary, I believe it offers a meaningful way to approach a multi-dimensional problem like AMR. More importantly, the use of service design methodologies—such as understanding user behaviours, co-creating solutions, and mapping complex systems—can be highly valuable in tackling AMR. It also raises important questions about which relationships within this ecosystem need to change and what interventions could create ripple effects throughout the system.

Beyond this, I think it would be fascinating to explore AMR through the lens of futures design, an approach that helps us imagine and prototype possible future scenarios, allowing us to explore how today’s decisions shape tomorrow’s world. Rather than just reacting to existing problems, it encourages us to co-create a vision of a preferable future—one where antibiotic resistance is better managed—and identify the steps we need to take today to move toward that future.

AMR is a wicked problem, and no single solution will fix it overnight. However, small but thoughtful interventions in key areas like antibiotic use can create ripple effects. By redesigning how workplaces support employee health, we can shift attitudes toward antibiotics, one company at a time.

—

About the Author: Arohi Dhore is a service designer passionate about creating meaningful services that drive change. Her approach is grounded in systems thinking, the Wheel of Behaviour Change, and a user-centred focus, enabling transformations in relationships between various stakeholders.